The past twenty-five years have offered boom and bust. There are lessons from the experience of these periods that apply to the current market problems. These lessons offer long term hope in a time when that appears to be in short supply.

“Life can only be understood backward—but it must be lived forwards”

Kierkegaard

I just learned that someone I know talked his son and daughter into converting their 401(k)s into cash. I do not think that they cashed out, I took it to mean that they swapped their current set-up from mutual funds to a money market. These kids have about 35 years to go before they retire. Of course, he has no experience with investing and almost certainly heard that that was what one was supposed to do – a classic mistake. I consider recommendations of this sort to be financial malpractice.

We are currently in a place that is not unfamiliar to me, as I experienced similar situations in 2000 and 2008. Both of these occurrences were different and each allowed me to learn lessons that can be used today. In this article, I explain why the above was exactly the wrong thing to do, examine the lessons learned years ago, and describe how they can be applied to the current financial crisis.

Financial Malpractice

Talking heads dominate the information that comes our way. Although their words may be well-intentioned, the standpoint from which they speak might not address your situation. Short term considerations may or may not apply to those investing for the long term, and one needs to distinguish between the two.

Active traders are probably collecting cash at this time, and those who feel bold may consider shorting stocks as they claw their way to the bottom. The next several months will be hard times for those who have only experienced the longest bull market in our history, and when earnings reports arrive with forecasts for the future, the market will compare this information to the current losses to see how much of the negativity has been taken into account.

This is where long-term investors distance themselves from the daily fire hose of information. In the case I noted above, the financial outlook of these two is long. The purpose of a 401(k) is to build resources for retirement, so in their case, by definition, these instruments will only be of use to these kids three decades from now.

They could benefit from these moves if they decide to move their cash assets back to stock funds at a time when the market’s value has fallen even more, but I fear that this will not happen. Most disastrous would be that this event clouds their judgment to the point that over the years their 401(k)s will remain in cash, which loses to inflation.

To make this work they need to watch the markets and get back in at the right time. If they are not thinking about the markets this time will pass without notice, so they will lose decades of compounding for those lost gains. The S&P 500 was not foremost in my mind when I was in my 30s, and is almost certainly not in theirs.

But it is not only this but the purchases will also be lost. However long the market’s value is depressed, those monthly purchases will be going to cash, as opposed to purchasing funds at depressed prices. Buy Low/Sell High is the investor’s mantra, and putting retirement funds into a resource that removes the former denies the latter.

With a 30-year timeframe for these two, the single important element is the eventual amount available to them when they retire. Finding a way to get to that point is made problematic when the Buy Low half of the investor’s formula is removed.

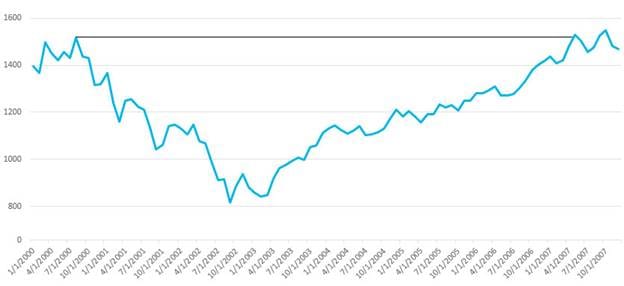

Lessons from 2000

The late 1990s was a strange time for investors. Companies with no earnings entered the market with huge IPOs and massive valuations. At the beginning of 1995 the value of the S&P 500 was 459 and five years later it had more than tripled to 1,468. The technology-laden NASDAQ rose more than fivefold. A “new paradigm” was heralded where the market would always rise and never go down. People believed this.

Until things collapsed.

Nearly half the value of the S&P 500 disappeared into thin air. Stock valuations rose to insane levels, as they had been priced for perfection. It is like stacking blocks without realizing that there is a point where one more block imperfectly placed will bring the whole system down.

This happened in October 2000 when Ravi Suria, a bond analyst at Lehman Brothers, issued a report cautioning against Amazon bonds. One of the things that I had learned in the late 1990s was that one should look toward the leaders, which at the time were Yahoo, AOL, and Amazon, and to forget about the small companies popping up everywhere. With the realization that one of the stable companies was anything but that, the stack of blocks fell.

The most important lesson I learned from that experience was that the markets always return to sanity … before they once again go insane. As imperfect human beings, we tend toward the influence of the crowds. The larger the crowd gets, the more attractive it becomes, and more people attach themselves to it in a self-feeding mechanism.

We tend to rationalize crowd behavior by imagining it being correct until it falls apart, at which point we pick ourselves up, find a new crowd to follow, and restart the cycle. Extremes get louder voices, louder voices lead, and the feedback loop continues until it can no longer sustain itself, at which point it collapses.

In the article Stock Tips Are Bunk I recommend that one should know why they buy. The lesson from the dot-com bubble was that when one’s reasoning to purchase stock is along the lines of “because it will make me money” they are exhibiting herd behavior. Having a clear understanding of a company’s fundamentals, and having specific expectations for its performance in the future distances one from the herd. Logic and numbers drive the decision, as opposed to the emotion of influencers. When you have rational reasons for making a purchase, you have those same rational reasons when it comes time to consider selling.

Stocks move on emotion, then return to logic before moving back to emotion. Sticking with logic evens out the ride. Let others ride the waves. Using logic based on facts separates one from emotion and irrational voices.

“Nobody ever made a dime panicking” – Jim Cramer

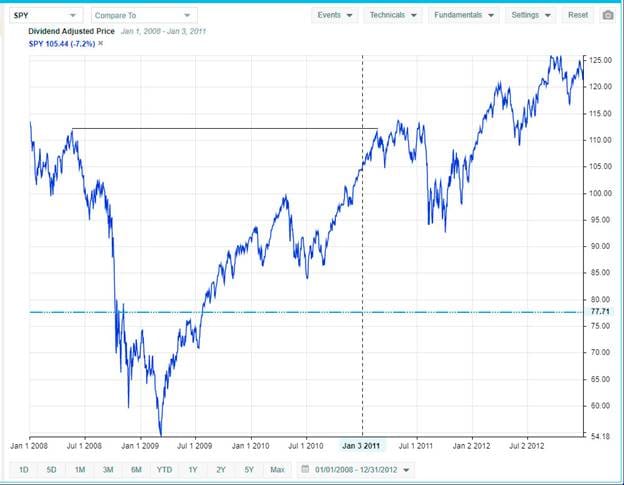

Lessons from 2008

The financial crisis of 2008 was the biggest financial threat to the country since the Great Depression. The S&P 500 lost more than half of its value in a very short time.

This was a different type of insanity. Banks bundled securities, the contents which were so complicated that even they had no clear idea as to what they contained. Interestingly, the market’s fall began with the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the firm in which Ravi Suria had been an analyst.

The US Senate issued a report stating that the crisis was the result of “high-risk, complex financial products; undisclosed conflicts of interest; the failure of regulators, the credit rating agencies, and the market itself to rein in the excesses of Wall Street”. Having recovered from its insanity, once again the market had gone insane.

While the dot-com bubble had been easily foreseen, the great recession was much less so, though the signs were there. We bought our house in 2000. We did not have enough for the down payment (the house cost 15% more than the maximum amount we had set, but we loved it and made do) so we took out a second mortgage at a rather high interest rate. In 2003 interest rates had dropped dramatically so I felt that refinancing made sense.

The first place I called did not want to speak with me, but the second was amenable. When they came to speak with us we were told that a second mortgage was not necessary because the house’s equity was sufficient. This stunned me since we had only owned the house for three years. They made it clear that they intended to immediately sell the mortgage, which made no difference to me as I didn’t care who received the mortgage payments.

There is no need to recount what happened to our financial system after that (though if you wish you can read about it here). However, I had noticed the oddity of our house appreciating so quickly, and whereas we had originally struggled to get a second mortgage, now people were eager to give us a consolidated loan to flip.

The lesson learned was that when easy money is found (in this case buying and quickly turning over mortgages and flipping houses) there is a counterbalancing entity that will bring this back to where it should be. In this case, easy money was held out to those willing to take it, but to keep up the scheme instruments were invented to mask the increasing riskiness. The cycle replicated itself to the point where it could no longer stand on its own and a final straw broke its back.

Like building debt with a credit card, in a zero-sum game the yin is the easy accumulation of things and the yang is the eventual payback. When people have found quick and easy ways to make money there is always a counterbalancing element, and its swing can be swift and severe.

“The punches you miss are the ones that wear you out.”

Angelo Dundee

Utilizing the Lessons during Those Times

As seen by the charts, stock prices took major head dives. Many people panicked and many of those people lost money. In 2000 I was somewhat, and in 2008 primarily, investing in dividend stocks through dividend reinvestment programs. In both cases, I had a set amount to invest each month, and every month I made regular purchases. I had invented the InvestMete strategy and used that to guide me on how much to send to each of my companies.

I know of people who decided to sell everything and refused to get back into the market. This was very unfortunate because they missed out on the longest bull market in history. I was fortunate to have understood that the market would come back eventually and that all of my purchases would have been made at bargain prices.

I had also eschewed an attempt to time the markets. Take another look at the chart for 2008. Had I attempted to time the markets I may have tried to get back into the market in October 2008 as things started to come back only to see them decline again, so I may have sold. I may have tried again at the beginning of 2009 as the market rallied, only to be spooked that summer when things headed south again. How many times might I have tried to jump in and out only to make disastrous moves at the wrong time?

In the DIRC Message Boards we almost celebrated when things went negative because we knew that our regular purchases of quality companies were like going to the bank when there was a sale on cash. These purchases were an assurance that we were buying low, and when the time came we would end up selling high. As it turns out, that is exactly what happened.

The most important takeaway from these two events involved the importance of making regular purchases. Return to the graphs above and look at the line from the high to the return to that high. In each case I continued sending money to buy shares each month and all of those purchases were made at a discount, so the same amount I had been parting with was resulting in more shares. Additionally, the additional shares were compounding during this time. Anyone out of the market throughout this period lost the ability to benefit from those advantages.

Utilizing the Lessons during These Times

Today I am retired and living from those purchases as I wait until the age of 70 to collect Social Security (receiving an additional 32% by delaying four years). But what is one to do at this point?

The answer to this question will vary from individual to individual. There are some universal answers, and one is to not move your 401(k) to cash if retirement is decades in the future. Will the market be higher in 2050 than it is now? Yes. Every purchase made from now until that time will not only come at a lower point but will additionally compound with reinvestment, which is the secret sauce to dividend investing.

Outside the obvious, what is to be done? I start my recommendation with a return to my post Perhaps It Is Not Time to Invest. In that article, I noted the importance of maintaining a balance of cash equal to three months of living money. We are living the reason for having that money – you will have the capital to pay bills, buy food, and make rent/mortgage payments the need arises. This is your rainy-day fund, and it is currently pouring outside.

If one is approaching retirement then that three-month timeframe should extend to six months or even one year. Assets that are relied upon for the coming year should not be in the stock market and this is an excellent example of that reasoning. Those who have everything in the market at this point are being required to sell shares at exactly the time they would rather not do so. Pulling from a year’s worth of cash offers a buffer to catastrophic events like the one we are all living through.

If you have retired then the more cash you have at your disposal the better. We wish to sell at a time of our choosing and for stocks, this is not the time. Bonds come after cash, then one needs to look at what in their diversified portfolio is next. If you have no diversification then you have no options.

The current situation is not something that will have us back to normal any time soon, so we are talking about recovery over the coming years. This means that a long term outlook is mandatory unless one is seeking to actively trade, buying and shorting stocks (the only stock I ever shorted was Trump Entertainment Resorts, and while that made me money, it also taught me that I did not have the stomach for that type of investing).

Finishing Up

If you have the resources, begin looking around to see if there are companies on sale that are of interest to you. I feel that while the core of a prudent portfolio should consist of stable investments, there can be room for a small amount of speculation. By small I am talking about the amount that one can afford to lose in a worst-case scenario.

Through events such as this, I note that strong companies, while carried down the river with everyone else, do come back. It is not difficult to find these companies. Think about it – which sectors are hardest hit, which companies within those sectors are hardest hit, and which of those companies have a handle on debt, a strong balance sheet, and name recognition? Think of companies whose products you might have purchased or services you may have considered one year ago but now would not touch with a ten-foot pole. Those are the companies to consider.

For those who insist upon trying to time the market, I suggest that we have a long, long way to go. I am writing this toward the end of March 2020 and am looking forward to / dreading the April earnings season. This is a time of great volatility, as companies report their monthly earnings and offer a look into the future. Some will get crushed by what they report while others will rebound, as more downside may have been cooked into the price than necessary.

If you look at the 2008 chart from Stock Rover you will see significant moves during these months as investors tried to figure the damage to companies. This will happen again. Determining the proper value of a stock is difficult in calm times, it is close to impossible when insufficient information is available. Will this earnings season show that too much was thrown into the downside or will it simply act as a wind to a fire?

For the long term dividend investor, these spikes up and down will smooth themselves out. Regular purchases will show to have been made at fire-sale prices and those inexpensive shares reinvested will grow more quickly. Act with information and logic, listen to yourself and wash your hands.