There are so many advantages to dividend investing that when I read about problems with the strategy, I tend to be skeptical. More often than not, identified problems are false flags and/or misunderstandings. I examine one such article, dismantling each issue raised, with facts.

I read a lot of articles about dividend investing. A number of them offer reasonable advice while a few appear to try to find a problem with this investing strategy. When I read the latter, I find that it usually concerns itself with problems encountered when one uses the method in the wrong way, like concentrating on high dividend stocks only. What I am seeking is an identification of flaws in the proper implementation of the strategy itself.

Other articles, however, make me shake my head and wonder why it was written in the first place. A while back I decided that the next time I encountered such an article I would write one myself and address their objections.

6 Problems with Dividend Investing is such an article. It begins with “you have probably heard at least a handful of “experts” praise dividend investing” and goes downhill from there, as the author, Taylor Schilte, likens the strategy to smoke and mirrors. As it was published in Kiplinger, a well-known financial magazine, I felt it my duty to examine each of the six “problems” the author identified to see whether or not he exposes a problem I had not previously considered.

1. Historic Performance

The majority of my article is concentrated on this subject, after all, if dividend investing is not one of the best means of investing in equities, then the rest is moot. We place our hard-earned money into the trust of companies we believe will fulfill our objectives. There is no one “best way” to do this, but some are better than others, so at least selecting one of the best means is imperative.

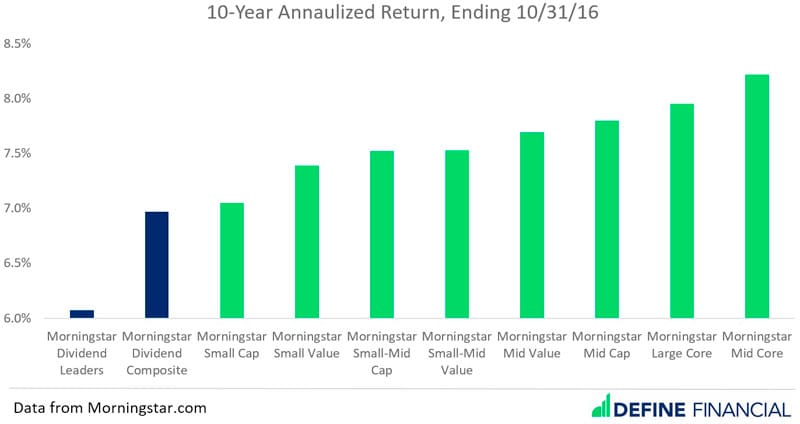

I start with the offered chart, which contains his entire argument that the historic performance of dividend stocks underperforms others grouped by market capitalization.

The problem has to do with the information on the horizontal axis. In an attempt to verify the numbers shown in the chart, I looked for the funds/ETFs/whatever that were listed. Unfortunately, even though the article is on a website, there are no links in this section to reference the values, just a single link to an article on his website that did not relate to the subject at hand.

Morningstar Small-Cap and Small Value are indexes, but I was unable to identify Small-Mid Cap and Small-Mid Value. Perhaps Mid-Cap refers to iShares? Having to guess the source of his numbers, I decided to toss the information and investigate the issue myself with clearly defined index funds, where anyone could check the numbers for themselves.

Again I want to emphasize the importance of this “problem.” If the author is successful with the argument that dividend investing is an inferior investment strategy, akin, as noted in the article, to smoke and mirrors (“the obscuring or embellishing of the truth of a situation with misleading or irrelevant information”), then it is game over, and there is no need to read further.

Vanguard is the originator of the index fund and offers funds that cover just about every range of companies imaginable. The author intended to compare dividends to groups of small, medium, and large companies, so I selected the following funds:

- VDADX – Vanguard Dividend Appreciation Index Fund Admiral Shares

- VTSAX – Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund Admiral Shares

- VSMAX – Vanguard Small-Cap Index Fund Admiral Shares

- VIMAX – Vanguard Mid-Cap Index Fund Admiral Shares

- VOO – Vanguard S&P 500 ETF (their S&P 500 fund is an ETF)

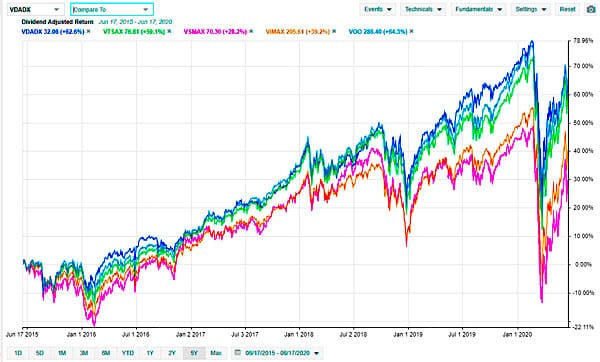

This group represents the spectrum well. In addition to the Dividend Appreciation index fund, the funds cover small, medium, and large companies, as well as all of them together. Charting the group in comparison over the past five years we see the following.

This chart shows that over the past five years small and mid-cap companies have underperformed dividend and large companies. That’s pretty much it.

Stock Rover has a nice feature that redraws the chart so that VDADX, the Dividend Appreciation Index fund, is a straight line, while the others are relative to that line.

This visualization is a little clearer. It shows that had one invested in all five funds five years ago, the Total Stock Market Index fund would have outperformed the Dividend Appreciation fund by 3.4%, but the other three would have underperformed, two dramatically so.

Not to beat a dead horse, but note how much time the straight line of VDADX stays above all the other four – it appears to be roughly half – so depending upon the timeline, the Dividend Appreciation fund may just as easily have beat the others.

Selecting a proper timeline is a tricky thing, and sometimes simply offers the results one wishes to see. Clicking the 1 and 2-year buttons on Stock Rover’s chart shows the winners to be VOO and VTSAX for the one-year time frame, and VDADX for the two-year time frame.

Vanguard’s website also offers information that we can use to compare these funds, displaying successful performance over the one, three and five-year timeframes (VDADX has not been in existence for ten years).

| 1 yr | 3 yr | 5 yr | 10 yr | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VDADX Dividend Appreciation Index Fund | -4.08% | 6.77% | 7.24% | — |

| VTSAX Total Stock Market Index Fund | -9.24% | 3.98% | 5.73% | 10.15% |

| VSMAX Small-Cap Index Fund | -23.33% | -3.27% | 0.42% | 7.84% |

| VIMAX Mid-Cap Index Fund | -16.65% | -0.26% | 2.08% | 8.86% |

| VOO S&P 500 ETF | -7.03% | 5.06% | 6.69% | — |

The point here is that however one slices things, the data I found looking at actual index funds do not correlate to the information in the author’s chart. Everything I have come across tells the opposite story, which is that dividend companies offer superior results.

Outside of my research, Hartford Funds offers a paper titled The Power of Dividends, where they compare dividend growers, dividend payers, non-dividend payers, etc. To summarize the article, dividends have a distinct advantage when it comes to offering superior annual returns.

The most important of the listed “problems” does not hold up to the scrutiny of actual numbers. Now on to the other “problems.”

2. Cost

The author states, “People who focus on dividend investing tend to ignore ongoing costs.” This statement would be news to just about everyone who has participated in The Dividend Investing Resource Center forums.

I founded the website in 2002 because The Motley Fool had decided to charge admission to their message boards, because I felt that people wanted a free means of exchanging information. Much of the past discussion has centered around problem dividend reinvestment programs that charge fees and how to obtain a company share for the least price. In my experience, dividend investors are more concerned with fees than others.

The only thing supporting the author’s assertion is an expense ratio comparison between iShares Core S&P Total U.S. Stock Market ETF (0.03%) and iShares Select Dividend ETF (0.39%). That’s it. There is no other supporting evidence.

To begin, an index fund will always be less expensive than one where a manager selects companies. In the year the article was written, the average expense ratio for an actively managed fund was 0.82%. Despite the horror the author shows for one paying more for the dividend fund than an index fund, the average for actively managed funds were more than twice as expensive, which is where I would find the real horror.

iShares Select Dividend ETF (DVY) would not exactly be my fund of choice. I did not include it in my article 4 ETFs for Dividend Growth Investors because it did not come close to the quality of the ETFs I highlighted. A quick comparison with VDADX shows why I did not consider it.

It would be wrong to discount the importance of fees, as they are important, so I will note that the expense ratio for VDADX is 0.08%. It is more than the index fund, but by the time we get to expense ratios this low, we may be pole vaulting over pebbles. 0.08% of $1000 yields $0.80, so the difference in a $1,000 portfolio between the index fund and the Dividend Appreciation Index Fund comes to $0.50. I am quite frugal, and even this does not bother me.

3. Diversification

Can we all just agree that diversification is important? I agree with the author’s insistence that diversification is imperative in a properly selected portfolio. Despite running a website that concentrates its information on dividend investing, even I do not have all of my retirement portfolio in dividend companies.

The third “problem” identified is that one should not place all of their funds in dividend stocks. Is there evidence that dividend investors put all of their eggs in one basket, whereas other investors do not? This “problem” is not a problem at all.

4. Performance Chasing

Again, the author states something with which I agree, but I am having a problem finding the “problem.” He states that buy-and-hold investments have great value, which is something I have been harping upon for decades.

Dividend reinvestment programs allow an investor to make numerous purchases of a company over a long time – that is their purpose. There is a dividend capture strategy where one holds a company for a short time, but almost by definition, dividend investors have a buy-and-hold approach.

The author concludes this section with the confusing non sequitur, “It’s only a matter of time until the dividend bubble follows the gold bubble, real estate bubble and tech bubble of previous generations.” Seriously? I invested during those last two recessions and can assure everyone that chasing an average dividend yield between 1% and 2% has nothing to do with what people were doing during those times.

5. Taxes

“The final problem with dividend investing is that it comes with hefty tax consequences.”

For many people reading this article, the exact opposite is true. The taxes paid on dividends (in the United States) are less than the tax rate, and for a single filer in the under $39,375 bracket (double that for joint filers), that rate is $0. In the year the article was written the average taxable income in the United States was $45,575, though the true average was certainly lower.

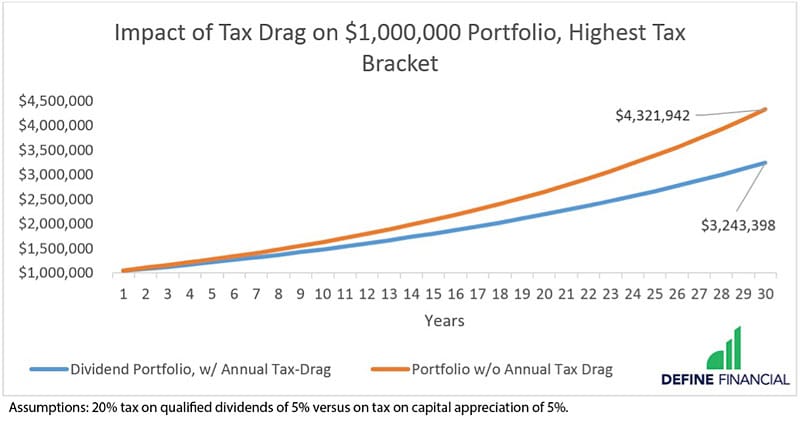

I was confused when reading this “problem” until I looked at the chart he presented.

The author is referring to those with multimillion-dollar portfolios. I admit to not having the knowledge (or need) to understand efficiency issues with multimillion-dollar portfolios, so in this particular case, I will cede the issue to the author.

6. Today’s Valuations

The final point is that one should buy low and sell high, and since dividend investing is so popular, it must be expensive. As evidence, the author references a Vanguard fund that had been closed. He is referring to the Vanguard Dividend Growth Fund, which is one I had at one time considered as an investment but decided against because of its high expense ratio (0.27%).

It is difficult to understand why the fact that a dividend fund had been closed for a while because of its popularity would necessarily translate to the assumption that all dividend funds are expensive to purchase. By that same logic, one might assume a negative connotation to the popularity of Peter Lynch’s Magellan Fund – though probably not, as I doubt that an annualized return of 29.2% over 13 years bothered holders of the fund. Popularity does not increase the price of a fund as a matter of course.

However, as evidence, he offers that Vanguard Dividend Growth Fund’s price-to-book ratio is 60% higher than the market average (today it is 45% more expensive). This is cherry-picked information. There are numerous means of valuing a stock, and no single number tells a complete story. According to the price-to-equity ratio, a value more commonly used, VDADX is 7% less expensive.

If this is an actual issue, the solution is simple, consider looking at the Dividend Appreciation Index Fund. There is no issue with a manager seeing more influx of capital than they can invest, the index follows the index, so there is no company choice or valuation issue. If one purchases individual stocks, they are already taking valuation into account and eschewing companies that are way too expensive, so that is not a problem.

Finishing Up

Of the six “problems” identified, there appears to be one that may be of consideration for investors who have multimillion-dollar portfolios. Those in that category would do well to have the advice of a tax advisor who can establish the most efficient path through the morass known as our tax system. For we “regular folk,” the tax issue when dealing with dividends is an advantage.

The next time you read an article look for the following:

- A clear explanation of the problem

- An issue that is relevant to you, the reader

- Links that support the author’s position

- Data that can be verified or replicated

Also, remember that incidental happenstances do not constitute an overarching idea. Single examples may be helpful with disproving specific assertions but do not necessarily establish a pattern or definition.

There is no perfect means of investing, and every direction has its warts. We all have our own needs and comfort levels, and finding the investing mechanism with the fewest disadvantages to those needs is the proper direction to take.